Alexander Lorber

In order to keep a clear path to the scene of an accident for the police, fire department and rescue services when there is a traffic jam on the highway, it is vital to form a rescue lane. Today, it is hard to imagine that in the early years of the Federal Republic of Germany, there was no standardized regulation on this in the Highway Code. Until Karl-Heinz Kalow wrote a draft law and sent it to the NRW state government at the time. At the time, he was the chief constable of the highway police in Münster. His proposed law has been legally valid since 1970. The "Streife" editorial team visited the now 81-year-old inventor of the emergency lane at home in Münster.

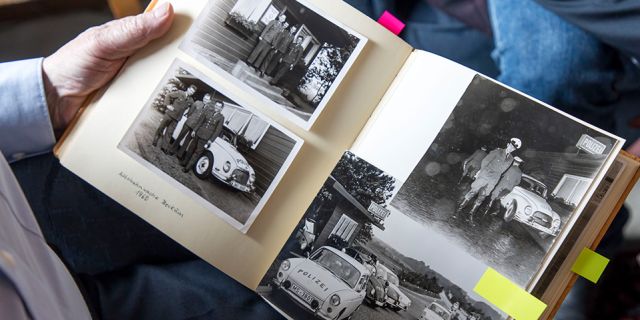

Karl-Heinz Kalow keeps his memories of his police service in his living room cupboard. Among them are his old shoulder badges and a small police car in model size. He takes an inconspicuous album with a leather cover from the shelf, in which he has carefully collected all the photos taken during his service with the traffic police. "Back then, they called us the 'white mice' when we drove along the highway in white patrol cars," says Kalow. There are also pictures of serious car accidents in the book, including rear-end collisions, burning cars and demolished trucks.

As a first step towards greater road safety, comprehensive central crash barriers were introduced at the time so that drivers could at least not drive into the oncoming lane if they were overtired. "The volume of traffic at that time was certainly not as heavy as it is today, but in the event of an accident, the highway was closed very quickly even in my day," recalls Kalow. He experienced a case where a truck at the end of a traffic jam was unable to brake in time and tried to swerve between the two lanes. However, the gap was too narrow. This resulted in a serious traffic accident and 14 vehicles were severely damaged. This accident gave the then 26-year-old traffic police officer an idea. There was no solution as to how the emergency services could get to the scene of the accident as quickly as possible in the event of a traffic jam. This should be regulated by law, Kalow thought.

An idea becomes law

No sooner said than done. He took pen and paper in hand and started making some sketches. How would traffic have to be regulated in order to give the police and emergency services enough space to pass through? There was indeed paragraph 48 in the German Road Traffic Regulations (StVO). It required drivers to clear the road for emergency vehicles. However, nowhere was it clearly formulated exactly how drivers were to behave. The young police constable therefore came up with a simple rule: Vehicles in the right-hand lane would have to pull over sharply to the right onto the hard shoulder, while drivers in the overtaking lane would have to pull over sharply to the left so that the middle remained clear for ambulances, fire engines and police. Kalow was not yet thinking about three- or four-lane highways back then. "During operations, we always found it annoying that road users were not prepared for our arrival," says Kalow. In a 20-kilometre traffic jam, losing a lot of time for the emergency vehicles can have fatal consequences for the injured. After all, every second counts in an emergency. In addition, the end of a traffic jam is a major danger point for further accidents. If drivers approach a traffic jam and slow down too late, further serious accidents can occur. If road users were to form an emergency lane, a vehicle could use the middle of the road to brake safely in an emergency. Kalow's proposal therefore has several advantages: It prevents serious accidents at the end of traffic jams and enables the police to quickly regulate traffic.

Karl-Heinz Kalow wrote a detailed justification of his proposed law and sent the letter to the Minister of the Interior's Committee for Official Proposals on March 29, 1963. But at first he heard nothing for a long time.

Green light for the emergency lane

A few years passed, during which Kalow's proposal was examined. Finally, in 1966, he received a letter from the NRW Ministry of the Interior. It stated that the then North Rhine-Westphalian Minister for Economic Affairs and Transport, Prof. Dr. Bruno Gleitze, had included Kalow's proposal in the draft of a new StVO. However, a final consultation was still pending. The final decision was finally made on March 14, 1967 - four years after his proposal had been submitted. It then took another three years before the new StVO came into force in 1970. As financial recognition for his proposal, Kalow received 100 German marks from the state of North Rhine-Westphalia.

"I was of course delighted with this small token of appreciation, but the main priority for me was clearly that the new regulation in the StVO would save many lives," says Kalow. Rescue lanes are now mandatory not only throughout Germany, but also in other EU countries such as Austria, Slovenia, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Switzerland. Unfortunately, not all road users still adhere to the legal rule. In July 2017, 18 people died in a burning bus on the Autobahn 9 in northern Bavaria. The driver of the coach had carelessly crashed into the trailer of a truck at the end of a traffic jam. 30 other passengers were injured, some of them seriously. The rescue lane was far too narrow, making it difficult for large emergency vehicles in particular to get to the scene of the accident.

Higher fines

In the meantime, politicians have reacted to the massive misconduct of many drivers. Anyone who fails to form a rescue lane for police and emergency services when traffic is at a standstill on the freeway must expect a fine of at least 200 euros. In the most serious cases, there is a fine of up to 320 euros and a one-month driving ban. Karl-Heinz Kalow welcomes the tougher penalties: "I can't understand how disrespectful some drivers behave towards the helpers and the police. Gawkers hinder the emergency services in their work and in some cases even cause further accidents." When Kalow himself was still an active police officer, he rarely experienced such a level of disrespect. "I've seen a lot of accidents and know how bad it can be for the victims. Experiences like that stay in your head. Quick help is urgently needed."

A little bit of pride

Today, Karl-Heinz Kalow, who spent more than 40 years in public service in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia and 37 of those years with the freeway police at the district president's office in Münster, is rightly proud of his contribution. The emergency lane was his idea and has saved the lives of countless accident victims. The 81-year-old has never made a big fuss about his achievement. When he tells other people about his invention, he is delighted to see their astonished faces. "I had a minor accident myself a few years ago. I told the police officer who was recording the accident how I came up with the idea of the emergency lane and that my suggestion eventually found its way into the StVO. She was very surprised and could hardly imagine that there was no legal regulation for this before."